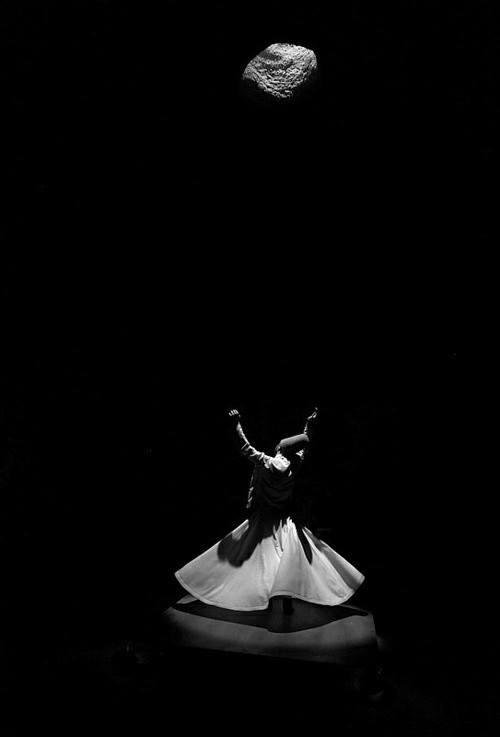

葦笛の詩

聞け、葦笛がいかに語るか

別れの悲しみをいかに訴えるか

私が葦原から切り離されて以来

わが悲しい音色で男も女もむせび泣く

私はこの切ない想いを打ち明けるため

別れで胸を千千に裂かれた人に逢いたい

己が本源より遠ざかる者はみな

合一の時を慕いて還ろうとする

どの集いにても私は哀しい音色を奏で

不幸な人や幸福な人と交わった

だれもが己が思いでわが友となったが

わが心の秘密を探った者はない

わが秘密は哀しい音色に秘められているが

目も耳もそれに気付く光がない

体は魂から、魂は体から隠されていないが

だれも魂を視ることは許されない

葦笛のこの叫びは火だ、風ではない

この火を持たぬ者は消え失せよ

葦笛に燃えついたのは愛の焔

酒を泡立たせるのは愛の情熱

葦笛は仲間から離された者の真の友

その音色はわれらの心の帳を引裂く

葦笛の如き毒と毒消しをだれが見たか

葦笛の如き同情者と思慕者をだれが見たか

葦笛は血に塗れた道の話を語り

マジュヌーンの恋の物語を語る

意識の秘密を識るのは意識なき者のみ

舌がもらす言葉の買い手はただ耳のみ

われらが日々は悲しみのうちに早く過ぎ

苦悶をともなう日々であった

日々が過ぎるなら過ぎよ、かまわない

比類なく清い方よ、留まり給え

魚にあらざる者はみな水に飽き

日々の糧なきものには日は長い

未熟者には成熟者の状態は理解できない

そこで言葉をかいつまむ、さらば

ジャラール・ウッディーン・ルーミー「精神的マスナヴィー」序章

(黒柳恒男 訳, 1980)

The Song of the Reed

Listen to this reed how it complains:

it is telling a tale of separations.

Saying, “Ever since I was parted from the reed-bed,

man and woman have moaned in (unison with) my lament.

I want a bosom torn by severance,

that I may unfold (to such a one) the pain of love-desire.

Every one who is left far from his source

wishes back the time when he was united with it.

In every company I uttered my wailful notes,

I consorted with the unhappy and with them that rejoice.

Every one became my friend from his own opinion;

none sought out my secrets from within me.

My secret is not far from my plaint,

but ear and eye lack the light (whereby it should be apprehended).

Body is not veiled from soul, nor soul from body,

yet none is permitted to see the soul.”

This noise of the reed is fire, it is not wind:

whoso hath not this fire, may he be naught!

‘Tis the fire of Love that is in the reed,

‘tis the fervour of Love that is in the wine.

The reed is the comrade of every one who has been parted from a friend:

its strains pierced our hearts.

Who ever saw a poison and antidote like the reed?

Who ever saw a sympathiser and a longing lover like the reed?

The reed tells of the Way full of blood

and recounts stories of the passion of Majnún.

Only to the senseless is this sense confided:

the tongue hath no customer save the ear.

In our woe the days (of life) have become untimely:

our days travel hand in hand with burning griefs.

If our days are gone, let them go!– ‘tis no matter.

Do Thou remain, for none is holy as Thou art!

Except the fish, everyone becomes sated with water;

whoever is without daily bread finds the day long.

None that is raw understands the state of the ripe:

therefore my words must be brief. Farewell!

O son, burst thy chains and be free!

How long wilt thou be a bondsman to silver and gold?

If thou pour the sea into a pitcher,

how much will it hold? One day’s store.

The pitcher, the eye of the covetous, never becomes full:

the oyster-shell is not filled with pearls until it is contented.

He (alone) whose garment is rent by a (mighty) love

is purged entirely of covetousness and defect.

Hail, our sweet-thoughted Love–

thou that art the physician of all our ills,

The remedy of our pride and vainglory,

our Plato and our Galen!

Through Love the earthly body soared to the skies:

the mountain began to dance and became nimble.

Love inspired Mount Sinai, O lover,

(so that) Sinai (was made) drunken “and Moses fell in a swoon.”

Were I joined to the lip of one in accord with me,

I too, like the reed, would tell all that may be told;

(But) whoever is parted from one who speaks his language

becomes dumb, though he have a hundred songs.

When the rose is gone and the garden faded,

thou wilt hear no more the nightingale’s story.

The Beloved is all and the lover (but) a veil;

the Beloved is living and the lover a dead thing.

When Love hath no care for him,

he is left as a bird without wings. Alas for him then!

How should I have consciousness (of aught) before or behind

when the light of my Beloved is not before me and behind?

Love wills that this Word should be shown forth:

if the mirror does not reflect, how is that?

Dost thou know why the mirror (of thy soul) reflects nothing?

Because the rust is not cleared from its face.

[The story of the king’s falling in love with a handmaiden and buying her.]

O my friends, hearken to this tale:

in truth it is the very marrow of our inward state.

[the prologue of Book 1 of Mathnawi by Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī]

(Translated by Reynold A. Nicholson, 1926

corrected several lines in 1930, 1937, and 1940)